When Epic announced its new digital store, one of its biggest selling points was that – a couple of times a month – the store wouldn’t be selling you anything at all. Instead, following in the footsteps of the model pioneered by Playstation Plus and Games with Gold on Xbox, the Epic Store does something that its PC competitor, Steam, doesn’t offer. On The Epic Store, users get a free game every week.

You can see the thinking behind Epic’s initiative – it helps them quickly get customers onboard and helps establish its storefront. And for gamers there is the obvious appeal of free games – and in fact, these games are really free because unlike Playstation Plus and Games with Gold, there isn’t even an online service subscription fee to pay in order to qualify for the free games. But is this a win-win-win situation for all those involved? When a game features in these free limited time promotions, does it work for the developer as well? Giving your game away for free isn’t the obvious starting point for developers looking to turn a profit for all that time spent on designing and building the game.

A league of their own

“Now that I look back it’s very easy to say that it [Playstation Plus] absolutely was the best decision. We make more now than we did at launch every month so absolutely it was. You know I think almost objectively you can say that it was a good idea at this point” – Dave Hagewod – Psyonix Founder

Let’s not beat around the bush because it’s no secret that – yes – giving your game away for free for a limited amount of time on one of these services can absolutely work for developers. And one of the best early examples of that in action is certainly Rocket League.

Rocket League launched on the Playstation Plus free game service in July 2015, at the same time as it was released on Steam for a fee (£15). It was an overnight success. Jeremy Dunham, VP of Publishing, talking to Kinda Funny Games back in 2016, said that Sony had warned Psyonix to expect a couple of million of downloads, and roughly 50,000 – 80,000 max concurrent players on its server.

Instead, the game servers crashed repeatedly from the huge numbers playing the game, and by October 2016, 22 million PSN accounts had played Rocket league, while sales on the console had reached 8 million. These deals are very secretive and esoteric – no one ever talks openly about the numbers; but you can have a good guess at how many people downloaded Rocket League for free when it was available on Playstation Plus using those numbers. A lot…

There are two ways to look at that. Firstly, you could say Psyonix left a lot of money on the table – especially at £15 a go. Surely a decent fraction of the 22 million players would have spent the money on the game rather than get it for free? You also have to factor in that Sony would have paid the developer upfront in the deal that made the game free for a month at launch, so Psyonix did get some income for the free players. But that amount would also have been based on the pre-release estimates of downloads, which at around two million is certainly far less than the reality. In theory, Psyonix missed out on a whole heap of revenue.

Or you can look at it with more positively, the free download meant that Psyonix reached a huge player base they never would have touched otherwise. Would they have even sold 8m copies on the console without the buzz generated by the free download. Jeremy Dunham has described how the company’s budget for marketing Rocket League was tiny, and that going with Playstation Plus let Psyonix pass the reins to Sony to do the brunt of the game’s marketing.

And there are a couple of things Psyonix have done really smartly, to make the game a massive financial success going forward even if revenue was sacrificed at launch.

For one, they made that decision to release the game on Steam simultaneously. As hundreds of clips of the game got shared online and it reached the top of streaming websites, the buzz created by the huge player base on PS4 certainly translated to sales on the PC. And it didn’t stop there. The game had successful launches on the Xbox and Switch platform subsequently, and of course was only available in its paid-for format.

The post-launch support for the game has been impeccable too. Alongside regular free updates, cosmetic-only DLC has shifted about once every quarter, giving Psyonix a chance to earn money from its huge player base on a regular basis. Just to throw a bit of soft anecdotal evidence in – I know I was a player who bought a couple of DLC offerings from Psyonix, not because I wanted them particularly, but it was my way of supporting the developers and saying thanks for the hours of free fun they had given me.

So every game should start free and grow from there right?

Not so fast. Rocket league is a standout story – and the biggest success story of a limited free launch strategy. But of course it’s not always like that. Velocity 2x from FutureLab games is a great example of how a free launch on Playstation Plus, even if successful, can be an issue.

Velocity 2x actually launched the year before Rocket League in September 2014. And it too was a free game on Playstation Plus and Vita at launch. Millions of people downloaded the game; to all intents and purposes, it looked like a runaway success.

But when the game got published on Switch in 2018, at a time when FutureLabs was desperately trying to fund a sequel to the game, it gave a totally honest call for support out to its fans.

FutureLab said if fans ever wanted to see a sequel to Velocity 2x, they needed to demonstrate strong numbers on Switch because otherwise no one would agree to fund any sequels. Curve Digital had agreed to publish the Velocity 2x on Switch but needed convincing by the sales numbers before agreeing to support a sequel.

Indeed, according to FutureLab, multiple publishers had got excited about the sequel when seeing early concepts and workings; and would also get excited about the critical success and the volume of players achieved by the first game. Unfortunately, interest would wane when the reality of the sales of that game were discussed. Velocity 2x – for all its millions of players on PS4 – hardly sold a copy on the platform. The majority of people who might have paid for it, had already got it for free. Unlike Rocket League, establishing that player base didn’t help make money further down the line.

The game did have DLC that potentially could have generated revenue from its PS4 player base – but both pieces, billed at the £2 mark – were released during the same month as the game. The availability of extra levels too soon after the release of the game does not give it the chance to breathe and create an appetite for more – maybe a larger DLC drop a few months later would have been a wiser approach and a better strategy for capitalising on its download success.

Furthermore, when the game – which had positive reviews and good buzz from the PS4 release – was launched on Steam in 2015, things didn’t exactly go to plan. Whereas Rocket League made good money on subsequent platform releases, when Velocity 2x launched on Steam, it coincided with the launch of Windows 10. Unfortunately, that resulted in a number of technical issues and bugs for the game that took many months to fully resolve. It completely destroyed any potential momentum on the PC platform because the game simply didn’t work.

So Velocity 2x needed to sell well on Switch in order to convince its potential publisher, Curve Digital, (or indeed any other publisher) to fund its sequel. I guess the fact that Velocity 3 is not currently being talked about in the pipeline from FutureLabs would suggest that didn’t happen. However, I should also note that Curve and Future Lab are currently working together on a game based on the popular Peaky Blinders series, so perhaps the relationship created by their work on Velocity 2x had some spin-off positive outcomes.

Modern market

There is another obvious difference between Rocket League and Velocity 2x that helps explain the disparity in the success of their Playstation Plus free game promotion.

Rocket League is a multiplayer game while Velocity 2x is a single player game. Online multiplayer games make a lot more sense to give away than single player games. Especially if the free period is at the beginning of the game’s lifecycle.

While Velocity 2x of course would have generated some buzz and positivity that got the name of the game out there and attracted new players, it could not do it to anywhere near the level that Rocket League could achieve. Put simply, it lacked the multiplication factor.

Rocket League had such shareable online clips of cool moments. It had hundreds of streamers and YouTubers playing the game showing it to thousands of potential players. And it was easy for players to show and play with their friends online and offline, who would then go get it themselves. It was a social game that marketed itself organically once you had a huge player base.

And on top-of that, the game was already earmarked to take the game-as-a service approach. There were ideas and plans in the pipeline for generating revenue off the existing player base, and its strategy resulted in strong sales on subsequent platform releases.

There is a decent argument that Rocket League might actually be a bigger and even more successful game if it was still free, and indeed free on every platform. If that were the case, the player base could be even bigger, with more people bought in and hooked, willing to spend money in other ways. That is exactly where we are now in the market. Some of the biggest multiplayer games, Fortnite and Apex Legends, are entirely free.

Which brings us back to Epic. Epic’s Fortnite multiplayer component is free to play on every platform it is on (and there is hardly a platform it’s not on) – and we all know that Fortnite has been a massive financial success. Notably, the single player portion of Fortnite, ‘Save the World’ is not free. Multiplayer games-as-a-service is a business model that makes sense; but single player games don’t have that same shareability among players. Giving your game away for free is clearly not the way to go for single player games – at least not at first.

When does making your singleplayer game free work for indie developers?

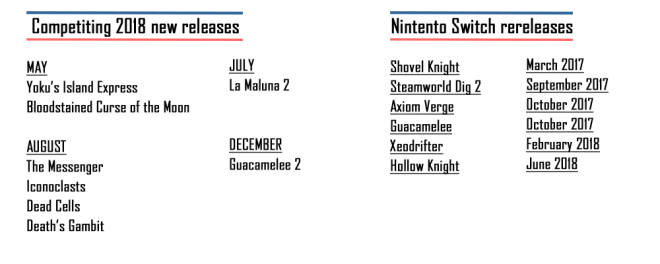

The games Epic is giving away for free on its store are not new games – and it’s largely the same on Playstation Plus and Games with Gold. The smart money says that it is further into a single player game’s lifecycle before giving it away for free brings benefits to developers.

Doing it too early cannibalises your own profits. Sure it might increase buzz about the game and get more people to play it, but if you do it too early, you’re stopping people who were willing to pay from doing just that. Whereas if you do it a year after release, you have a chance of drawing in new players to your games – and to your DLC revenue stream – that were very unlikely to play the game in other circumstances.

What’s more, if you do it not too long before the release of your next game, then you are adding another layer of smarts to your marketing. A free game can help establish trust and build positive feelings about your studio and your forthcoming games. Then when your new game does launch – your audience will have gained a bump in its potential size. Those who enjoyed the free game are far more likely to buy the new release now they know the quality of your work.

And of course, making your game free on these services doesn’t mean you’re not getting some revenue for the giveaway. As discussed earlier, the details of these deals are kept very secret within the industry, but it is an additional source of income.

“The impact was definitely worthwhile. Not huge, but worthwhile. Going free in the later parts of the game’s life cycle can give you some nice revenue boost.” – Jakub Mikyska, CEO of Grip-games

But the goodwill and market buzz you can get from the giveaway is what you are really after when making your game free for a limited period. You’re sacrificing revenue for intangibles. But the vast majority of that ‘sacrificed’ revenue was never going to come from the players who habitually download games for free anyway.

Of course, there is a danger to all this – and that’s why developers and the platform holders need to be careful. Creating an environment where gamers believe that if they just wait long enough, everything they want to play will become free eventually is a little dangerous. And we have certainly seen that cautionary market adjustment in the last few years, with the free game offers on Playstation Plus becoming noticeably smaller.

Epic with its new storefront needs to be a little wary of that danger. Creating an expectation of virtually limitless free games needs to be avoided. And studios also need to think carefully about how often they sign up to such deals. But securing the right free game deal, at the right time, can certainly bring advantages and be very worthwhile for all concerned – even a single player game.

But if you are developing a multiplayer game – the success of these free game promotions and titles such as Fortnite and Apex seems to suggest that making your game free all the time could be the modern and smart way to go – as long as it is coupled with a revenue plan to turn the player community into a viable income stream.

Free game promotions shouldn’t mean that developers are giving away profit potential. For that initial ‘gift’ they get a larger playerbase, a wealth of goodwill and exposure, and an additional fee from the publisher. It’s what they do with that kick start that matters; and it’s also important that the industry as a whole ensures these deals remain tactical incentives and don’t become the accepted business model.