Chasm is a metroidvania game that uses procedural generation to make each playthrough a unique experience. The building blocks are the same, but the layout of the game is different every time.

Hence, it’s a metroidvania game that you can play over and over again because the feeling of exploration that is key to the genre is always preserved. You can imagine as a child, the game’s director, James Petruzzi, wishing he could repeatedly play through the likes of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (a clear inspiration for Chasm). The tight controls and gameplay would remain, but the layout would jumble up – the old becoming new each and every time.

You see, in 1997, Castlevania was a 2D side scroller at a time when much of the industry was moving on to 3D. Arguably, the pinnacle of the metroidvania genre had arrived just as the genre was abandoned. It was 2001 before another 2D Castlevania hit consoles. In the meantime players were subjected to lacklustre 3D iterations and, what’s more, that 2001 game was only a port of a 1993 title that had previously been marooned on the ill-fated Sharp X68000 home computer.

It’s easy to see why a fan of the genre, starved in his childhood of the kind of games that captured his imagination, would set about creating a game that would let players fill the void. While waiting for the next metroidvania, they could play Chasm as much as they like – every time exploring a new map, with enemies in new locations and hidden treasures that are actually hidden again. In theory, Chasm is the eternal metroidvania. That’s what James Petruzzi wanted to create with his independent studio, Bit Kid games. The developers set out to make the game they wanted as kids.

Petruzzi clearly wasn’t the only kid desperate for more castlevania and more metroidvanias growing up. That was evidenced by the nearly 7,000 people who backed just the idea of Chasm by the end of its Kickstarter campaign in 2012. In fact, during the campaign, it received 70,000 votes on the Steam greenlight process. Petruzzi was right – there was an audience for games like Chasm. The kicker is, there is also a raft of other developers who love the genre and are eager to make their mark as well.

You don’t have to wait that long these days till the next metroidvania genre game hits shelves and online store fronts. It’s certainly not like 1997 anymore. When the Kickstarter for Chasm kicked off in back in 2012, metroidvanias might have been a bit rarer, nevertheless the 2D art style and sidescroller gameplay was already a firm favourite of many indie developers.

All of which meant that by the time of Chasm’s launch in July 2018, it found itself navigating a release schedule full of other metroidvania inspired games. In the five years it took to get Chasm from Kickstarter campaign to commercial release – many other successful metroidvanias hit the market.

So where did that leave the game hoping to be the metroidvania you can play again and again? After all, how many metroidvanias can the gaming market support?

Why developers keep coming back to metroidvanias?

Before we even attempt to answer those questions, it would be good to understand why there are so many of these games on the market right now. What is it about the genre that is so enticing to smaller development studios and independents?

First off, I think it’s clearly a matter of available resources. Back in the 80s and 90s the genre was on the cutting edge. Today, a 2D side scroller is well-trodden ground. It’s a cheaper and easier genre to make. Don’t get me wrong: It’s still not easy to make it good – but you don’t need a team of 3D animators, you don’t have to create huge 3D environments and there’s no 3D physics engine. It’s definitely not easy, but it’s a genre that can be realistically attempted by a smaller team.

And of course, as we have already covered, it’s a genre that many of today’s emerging developers grew up loving. In metroidvanias, developers can flex their muscles and experiment with lots of different aspects of game design. They can create a game with a strong narrative and a real sense of place. They can delve into the design of exploration, platforming, and combat. They can include secrets, collectibles, puzzles and imaginative character development. While these are all elements that can be applied to indie metroidvania games, they can equally be applied to the very biggest single-player games that hit the market.

For example, everything described there, could be applied to last year’s game of the year: God of War. I’m obviously not the first person to recognise this – but God of War is essentially a metroidvania game that is built in the 3D space. Whether you’ve got the biggest budget in the world, or the smallest, there is something about the core elements of the metroidvania experience that draws in both players and developers.

Creating a 2D metroidvania is a way for smaller developers to explore all the things they love about single-player games in a manageable way. It’s no surprise there are so many developed.

The Kickstarter problem

There was a short period of time in which Kickstarter was a viable option that you would suggest to new development studios. Frankly, that time has gone. But back in 2012, for Chasm’s creators, it was a route to market that made sense. And there are some things about Kickstarter that certainly worked in Chasm’s favour for its marketing over the five years of its development.

The platform gave the studio a clear way to build an audience for its game and connect with its fans. A really important part of marketing is to start early, and Kickstarter let’s you do that. It’s a convenient way to maintain high communication with fans. You can take them on the journey with you and build yourself an audience from the get go.

That interaction can be a double-edged sword however. Particularly if your game takes five years to develop, a lot longer than planned. If delays became apparent in the development – and you hadn’t started out as a Kickstarter project – you could perhaps adapt your messaging. You would release information within a timescale suitable for you and give updates at your own pace and discretion.

The problem with Kickstarter is you have a couple of thousand of your most hardcore fans, who have already given you money, who you need to placate. Not all of them will demand or expect regular updates, but enough of them will and – to be fair – they are entitled to them when you have gone down the Kickstarter route. They’ve funded you before you’ve delivered anything concrete.

What that means is that you can get sucked in to doing five years of intensive marketing – when maybe if the game was entirely privately funded, you would hold back at times, push at others. The long delays in development didn’t help Chasm. The studio would at times push hard on the marketing, thinking release is only a year away – when in reality it was two. Chasm’s strategy would no doubt change if Bit Kid had foreseen the actual timing.

In 2014, Dan Adelman, formerly of Nintendo, joined the team. He helped Chasm get on top of this problem, and in one interview spoke about this issue:

“With Chasm, once we realized it was gonna be a long time before the game actually ships, we deliberately slowed down our marketing reach, We stopped giving intermediate builds to YouTubers and Twitch streamers because you can’t keep the heat on high all the time. At some point, there’s fatigue and people start to tune it out.”

Adelman spoke to how a developer like Firaxis with Civilization can spend years working on a project in the background, with its audience never seeing the convoluted messy development path. It can then announce the game a year before, and launch an exact and deliberate campaign that ramps up to release. But because Bit Kid games needed to build an audience and secure funding, it simply couldn’t do the same – it had to take the audience along for the ride with them from the very start.

You might not want to reveal too much to your audience, but they need reassurances pretty much every month that the game is being worked on. With so many people burnt by failed or fraudulent campaigns – it’s kind of a necessary duty of care. In fact, Chasm delivered more than 70 updates on it’s Kickstarter page during development.

If it wasn’t for those pesky competitors

Chasm was released on the 31 July (16 July for backers). It coordinated with Sony and Valve to find a date not too crowded, that also left the press time to write reviews. Bit Kid also sought to coordinate somewhat with other similar games, because the situation could have been much worse.

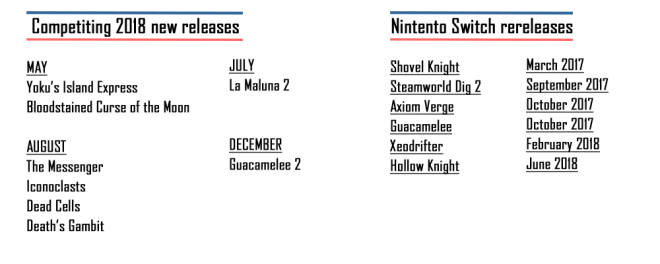

Other similar games did come out near the time of Chasm, and it was kind of unavoidable. What didn’t help Chasm – or the other new titles – is that the Nintendo Switch had proven itself as a great home for smaller indie games during the previous 12 months. This led to a number of developers porting established titles over to the Switch. Chasm didn’t only have to compete with other new and similar games, but also the re-release of some stand-out metroidvania titles on a platform perfect for them.

The months before and after Chasm’s release were full of similar games:

If you like Metroidvanias, there was no huge chasm of empty space. And the title that was perhaps the biggest problem for Chasm, was Dead Cells by Motion Twin.

Bit Kid might have got the jump on Dead Cells by releasing earlier, but must have been wary of the competition from the title at a very early stage. Dead Cells is a slick, fast and challenging game that controls and plays exactly how you would want it too when you pick up the controller. Its hook is that it adds rogue-like mechanics to the metroidvania genre. It procedurally generates the game world from death to death, not playthrough to playthrough, like Chasm. When you delve into the impact that has on actual gameplay, it’s not a case of ‘one-upping’ Chasm’s hook in my eyes. It actually makes for a completely different experience. You could even argue that dead Cells is not a metroidvania at all once you look beyond its initial perceptions. But the fact it even needs clarifying is ultimately damaging to Chasm’s key message.

So Bit Kid had a competitor in the shape of Motion Twin’s Dead Cells, doing its own take on procedural metroidvanias. Even if the two games, once you sit down, are very different – that is a marketing issue. You’re going to be drawn into comparisons you might not want to make.

And as it became clear that Dead Cells would be reaching market in a similar timeframe to Chasm, I’m sure there was an overwhelming sense of frustration at Bit Kid games. But the game had been delayed so many times previously, there was no justifiable way the company could take another hit and press pause once more… Instead it found a fairly decent window that gave both games a modicum of breathing room. Chasm got out first, which was probably a good thing, but there was yet another twist in the tale to the release of Dead Cells that propelled the game’s marketing to heights Bit Kid and Motion Twin could never have foreseen.

If you keep tabs on the gaming industry, it’s a story you could not have missed. IGN, the biggest and best known game review website, had to take down its review of Dead Cells when it emerged that its chief Nintendo editor had plagiarized his review from a small – now slightly bigger – Youtube channel, Boomstick Gaming.

IGN promptly fired the editor in question for the major ethics violation, but unfortunately for the company, a closer look at the back catalogue of reviews found that the incident was far from a one-time thing. A whole host of plagiarized content had to be removed from the site.

It was big drama and it was big news. It was terrible terrible terrible for IGN… bu, for the developers at Motion Twin – well – they hit the jackpot in a way that could never have been anticipated.

Suddenly, Dead Cells was part of the number one story on every game website, on every forum, every podcast, and every Youtube channel. Everyone was talking about IGN’s review, and subsequently, everyone was talking about Motion Twin’s game. And of course, it didn’t take long in most conversations to get to the – “oh and by the way, Dead Cells is a really good game” – part of the debate either.

The amount of unpaid natural coverage and exposure Dead Cells received was phenomenal.

Whereas Chasm has less than 50,000 owners on Steam, Dead Cells has more than one million. Of course that’s not solely down to the IGN controversy – but damn. For those of us who believe in the power of marketing, and the effect and difference that we can make, it’s a humbling reminder that some things are just totally out of anyone’s control.

Big enough market?

So is there a big enough market to support a game like Chasm in the face of such intense competition. Yes. But I carefully posed that question as ‘is there’ rather than ‘was there’? You see, it’s an ongoing battle if you want to make an indie metroidvania game a success. The job is not over for Bit Kid. To reap the rewards of it endeavours and make the adventure worthwhile, Chasm needs to keep slowly and surely bringing in the cash over the next few years, ensuring more and more players slowly discover it by word of mouth and through sales on digital fronts.

The guys over at Bit Kid are certainly doing a great job of keeping the lights on post launch. And it makes sense. When something took you five years to make, you don’t just abandon it straight after its launch period. Especially when Chasm did not release to huge fanfare, swathes of positive reviews, or catch a news break like its competitors.

Chasm at this point has sold somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000 copies on Steam. And it sells for £15 pounds. Of course steam gets a cut of that. And we don’t know how many copies of the game sold on PS4, Xbox, on the humble store, or on Nintendo Switch (where Chasm released in October of 2018, following the path so many other metroidvanias had trodden).

But if we very roughly estimate another 50,000 copies were sold on those platforms. Take away platform and publisher cuts, account for games purchased during sales, and you can start to take a rough guess at how the game has done. I think it’s safe to say the revenue for the game was pushing close to, if not over, one million – but it’s certainly not getting close to the tens of millions.

For a small studio, it’s likely enough to keep the lights on and adequately pay the developers for their five years of work. The company is unlikely to rapidly expand or grow off the back of Chasm, but as long as the game keeps bringing in a steady income, it should earn and learn enough from Chasm to come back with another project. I really hope so anyway.

Because even though it is a crowded market, it is a market that can support multiple games. We’re not talking about an audience exclusively of kids and teenagers, who to generalise for a second, are busy playing the latest battle royale game.

The target audience here is older. It’s an audience who have a disposable income. And they probably don’t have as much time as they would like to play games as they used too. A game at an accessible price range that doesn’t take 50 hours to play will be appealing to many such players.

Chasm is not going to age badly in the next couple of years – after all, it’s already trading on nostalgia. The market might be rammed right now, but in the future, more players will be looking to scratch that metroidvania itch. And when they’re ready, Chasm will remain a viable option.

That’s why it’s very important Bit Kid doesn’t go quiet on Chasm while it works on whatever comes next. And so far it hasn’t, still answering questions about the project on Twitter and on Kickstarter. Bit Kid is still updating and improving the game, and posting monthly updates on its website. Perhaps the best example is the translation work the team has been undertaking in the last couple of months, expanding the appeal of the game to more foreign markets.

If metroidvanias are all about retracing your steps and going back to areas when you are stronger, so is the marketing of one in a crowded space. Bit Kid needs to keep going back to its potential audience, with stronger messages and with new tactics. It has to keep finding new players and keep grinding away to keep the fight alive.

Great Read! Very Enjoyable and I love the language-I felt like you were in the room explaining to me.

I do feel that especially over the last 2 years or so the industry has become over saturated with these types of games with only about 4 or 5 being recognizable. Sometimes a game studio doesn’t even need to really change the genre- I believe metroidvanias really can’t go wrong but for me its more of the laziness with game flow/style and artistic choices. I mean, look at Guaccamelee. in its soul its a metroidvania but the reason it hits home so well is because of the art style and flow of game actions. It is very difficult for indie developers to copy the 16-bit style and successfully sell a game unless it is crazy good like dead cells, and most of the indies don’t have the time or budget to make it as good as possible. As far as I’m concerned the genres that will never fade are metroidvanias, collect-a-thons, fighters, and racers. Everything else will come and go.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Luke,

Great point about Guacamelee – standing out in this day and age is a lot to do with that initial perception/look. It and hollow knight both strive in that department with their art style.

LikeLike

There are way too many metrovania games, and I hate most of them. Steamworld dig is good so is shovel knight axion verge and guacamelee. They go into their own style have unique game play features and good story and consistent art and are well thought out.

Every other metrovania game is just a cheap knock off. The game play is clunky repetitive and the art is just bad and the story is bad. They make the story vague because they had no talent to make a story or they wanted to be artsy. The music might be good but a game is more than just good music.

The market has become saturated with two bit hacks who want believe that they are talented and just oversaturate the market. Just do a simple search and you can see all the shovelware games that flood the market.

They are not creative at all and are a waste of space to me.

LikeLike